- Depending on soil moisture content in your area “Plow Layer” compaction at depths < 8”or “deep compaction” at ≥ 8” may have occurred this season.

- Detect compaction using a soil probe, tile rod, or cone penetrometer noting depth and horizontal expanse.

- Choose the right tillage tool for the job. Shallower compaction can usually be relieved with normal tillage equipment while deep compaction requires the use of bigger more aggressive equipment.

- Insure that soil conditions are right at the time of tillage to avoid further damage.

- Bulk density, a measurement of dry weight/ volume of soil, can be used as an indicator of compaction and varies with the specific soil texture.

- Completed tillage pass, in addition to natural freeze and thaw, wetting and drying cycles will eventually return soil to a healthy bulk density.

Soil compaction can take several forms in cropland. The different types of compaction include plow layer, deep compaction, wheel track compaction, surface compaction and sidewall compaction. This article will focus on plow layer and deep compaction, their causes and management.

Plow Layer compaction develops with equipment traffic and use of certain implements, such as the large disk. A well-defined layer develops just below the depth of tillage. Plow layer can be detected with a soil probe, tile rod, or cone penetrometer. This layer interferes with water infiltration and root penetration. Deep compaction is the general compaction that develops below the eight to ten inch depth in the soil. This compaction is usually caused by heavy equipment loads on moist soils. The compaction radiates downward from the point of tire contact with the soil and can sometimes be detected twenty inches deep or more. Varying degrees of soil compaction can occur in between these two types of soil damage, but it doesn’t necessarily change how to manage them to better the situation.

Eliminating compaction in a field can take time and depends on the degree to which the soil is compacted. Shallow plow layer compaction can be easily removed using general tillage to shatter the zone and size the soil when not reaching a depth outside tillage equipment depth. Deeper soil compaction below what is the normal tillage zone may require more time and bigger tillage equipment. Shallow or deep tillage doesn’t usually eliminate the complete effects that compaction has had in a field. The combination of opening up the ground with deep tillage and allowing cold air/frost to penetrate deeper in the soil profile is the best method to relieve compaction at depths greater than the tillage zone. Obviously while the soil is recovering from the compaction incident, refraining from traffic or livestock grazing on the field will help with its recovery.

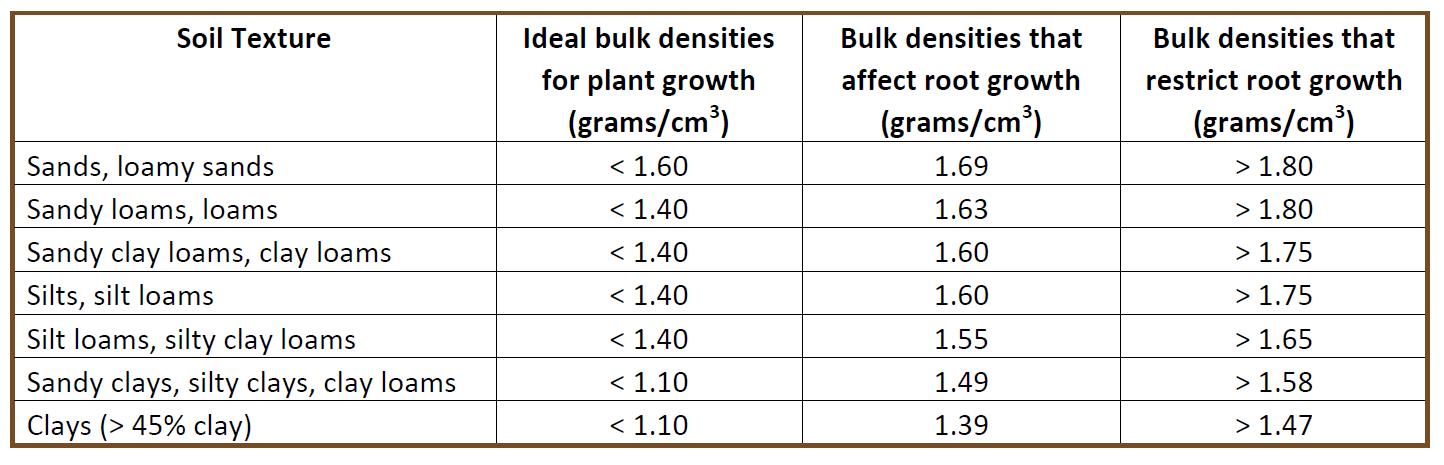

The soil conditions at the time of tillage must be dry enough to cause the soil to shatter and not allow tillage equipment to simply cut slots in the soil. After multiple freezes and thaws, repeated wettings and dryings (which causes shrinking and swelling of the soil), the soil will return to an acceptable “average” bulk density. Most often this will not occur in one growing season and in severe cases it may take multiple seasons. Soil bulk density is a dry weight by volume measurement defined in g/cm3. A specific probe is used to take a sample about the size of a soup can. This sample is dried to a constant weight and then weighed. Knowing the volume of soil sampled (in cm3) and the weight in grams, the g/cm3 can be calculated. A compacted soil will have a greater bulk density than it should for its soil texture (Table 1). This higher bulk density will change the soils permeability, making it more difficult for roots to penetrate the soil and create an oxygen starved environment necessary for good soil nutrient uptake, to name a few items. The soil bulk density at which root penetration becomes restricted varies with soil texture due to their differences in aggregate size and density. Table 2, below, lists bulk densities for varied soil textures at which root growth can be affected.

Table 1: Source: From the Surface Down. An Introduction to Soil Surveys for Agronomic Use. William D. Broderson (NRCS Document)

Table 2: (below) Source: USDA NRCS “Soil BulkDensity/Moisture/Aeration”